Ron Crittall [UK Financial Times] meets a woman to whom hippos, threatened and abandoned during the drought of 1991/92 owe their lives.

—oOo—

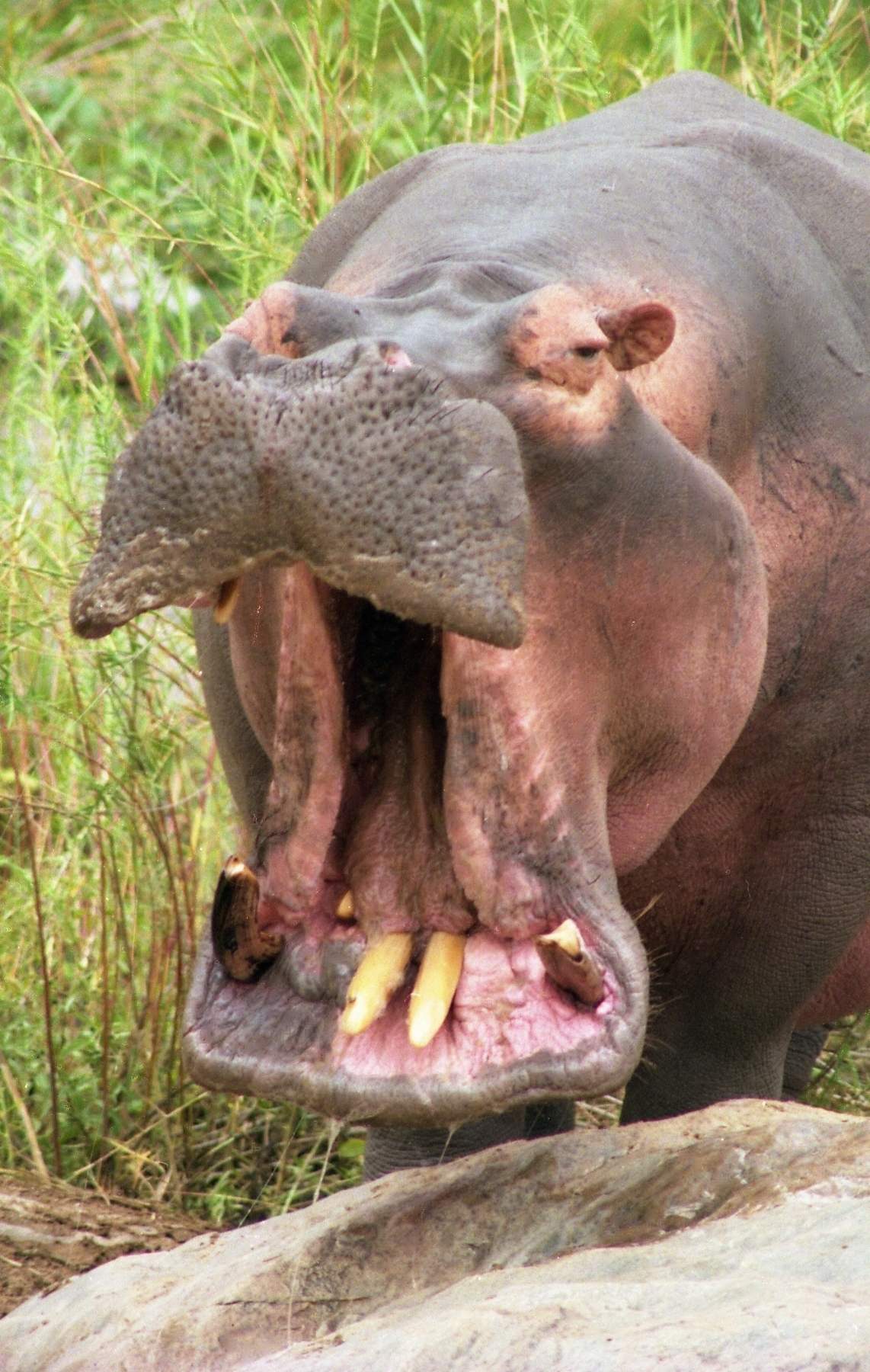

It was dusk, Karen Paolillo sat on the banks of the now flowing Turgwe River, in south-east Zimbabwe, talking to the pod of hippos grouped attentively in the water below. “Here my guys. Bobby, come on, my boy. Come on, Bob. You see how calm they are? There’s no fear there – that’s fabulous – you would never have got that a year ago”. The previous day we had an indication of how special these hippos are, when they clambered out of the water on to an island– in our presence. Hippos may be large but they are timid when in the presence of humans. Their standard reaction is to get in — not out of — their patch of water, and submerge. But these hippos owe their lives to Karen. They have learned to trust each other during the last three years since the drought which hit Zimbabwe in the 1991/92.

The south-east of the country was almost a desert – there was no water or grass, and wildlife and stock were dying everywhere. There were efforts to rescue cattle, elephants, rhino and other game — but not the hippo.

Karen was living above the Turgwe River with her French husband, Jean-Roger. It was not their land; they were staying where his job as a geologist had taken him.

“I approached the one landowner of the hippos. Here wildlife is owned by the person whose land they are on – and asked what’s going to happen to the hippo”. He replied, “I’m awfully sorry – We’ve rhino here; it’s an endangered species, and I’ve got my livelihood, the cattle.” He did agree, however, to Karen trying to get sponsorship to save them.

The first problem was whether they could be fed, and if so with what.

Karen approached Clem Coetzee, the fundi (Zimbabwe’s word for expert) of wildlife management. He could only make suggestions because nobody had fed hippos in the wild before.

Then a local sugar company produced a survival ration as their contribution to drought relief. It was a mixture of molasses, cotton-seed, sugar cane, vitamins and urea.

Karen said:

“Then – it’s a long story and it was happening quickly; it was a major rush — the next thing was to get them to feed. These are wild animals; they’re not used to being fed by man but they were starving. They’d actually dispersed from the river and were looking for food. We (my husband and I) put food down in the river, and we waited. We put molasses on the food to attract them.”

She began on March 3rd, and on the 18th they began to feed. “From the minute they started feeding — I had four at that stage — they started coming back. It was as though word went out– I don’t know how– and eventually I was feeding 11.”

Then her husband’s job required him to move away. They decided that Karen would stay at the camp and feed the animals. By then she had secured sponsorship of about ZIM $50,000, an amazing achievement given the demand for help of any sort. “I was responsible to a lot of people, and for me the priority was these animals,” she said.

Not only was she losing the help of her husband, Jean-Roger, but she was also losing the use of his four-wheel drive. This meant that Karen would have to feed the animals from home, rather than by the river. So, before he left, they managed to persuade the hippo to come up the steep bank, all the way to their camp.

It wasn’t just the feed that was a problem. “The river in front of us was totally gone,” said Karen. “We bulldozed here but we hit rock bottom. The British animal charity Care for the Wild International paid for all the water we put in for the hippo. We had to transport water from 16 km away by the use of piping and borrow it off other people who needed it. We had to put in troughs for drinking water; we had to put in a pan (a depression to hold water, cemented and large enough to allow the hippo to submerge themselves).

“The drought broke on October 13th 1992. That morning I took a photo of wet hippo feet in the mud on my way down. They were in the river and they were like children. That’s the only way I can put it. They were bouncing like dolphins in the newly flowing river and they were unbelievable.”

The breaking of the drought and the return to normal for the area, the river and the hippo, did not end Karen’s involvement. “I’ve become addicted. In fact, my husband reckons he’d rather I had an affair then have me feeling the way I do about the hippos,” she said.

Jean-Roger and Karen have now built a permanent home above the Turgwe River, but he can only be there for about five days in every five weeks. Karen has created the Turgwe Hippo Trust to look after the future well-being of the hippo.

One of the main tasks is to prepare for the next drought, which will inevitably come. While more artificial pans will have to be built, the top priority is to drill a borehole, which will not be cheap or easy. This is remote bush, 465 kms from Harare, the Zimbabwean capital.

Karen has started a behavioral study of the hippo. Another Trust aim is to restock with hippo. The Conservancy is already bringing in rhino, elephant and buffalo. Karen hopes that, where hippo are under threat elsewhere in Zimbabwe because of culling or crop raiding, they can also be rescued and brought to the Conservancy.

The Turgwe hippo that Karen hand-fed have now dispersed, except for the group below her home. They have been breeding and have produced two babies since the drought.

Bobby’s the big bull there; Blackface is the mother of the little one; “Three,” who was born on November 3rd 1993. That’s “Lace” in the background, and Tembia is the other calf her son. He’s just over a year old and he’s hiding – you can just see his nose. Tem! Come on Tembia! No, you don’t want to show yourself.”

“Goodbye, guys. I’m going now. Goodbye, Goodbye.” Karen stood up and walked into the bush, out of sight of the river and of the hippos.

A pause. Then Bobby spoke.

HUNH ..HUNH..HUNH….HUNH…HUNH…HUNH.

0 Comments