Yesterday, the 4th of February, the day commenced like any other. But by evening I knew I had lost the most important hippo of all of the Turgwe Hippos. Bob the bull had died.

Bob was the largest hippo bull in the entire Turgwe River. He was also probably the oldest. He weighed around two and a half tons and in his life he had sired many calves.

In the 13 years that I have lived here, he had always been the most dominant of the hippo bulls. Bob had been the “boss” and, for me personally, had also been the most special of all of the Turgwe Hippos.

It was through knowing Bob and learning from Bob about hippos that all of the projects that this Trust has achieved and everything that has happened here occurred. Bob taught me so many things; Bob allowed me into his space.

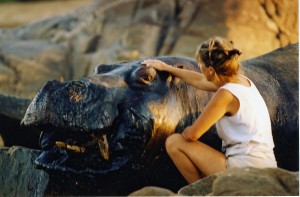

A wild African Hippo Bull let this human female be part of his daily life. I was accepted by Bob as connected to him and his family.

It began in 1990: We moved here to the southeast Lowveld of Zimbabwe and 15 hippos lived in two small groups below our camp. Bob was the first hippo I met. In fact, Bob wanted to kill me when I first came into contact with him.

You see, this area then was a sport hunting area and safari clients had shot hippos for sport! Some of Bob’s family had died at the hands of man; Bob was not overly impressed with humans.

Being the dominant bull, his stance was one of assertiveness: large gaping yawns with his eyes narrowed and the expression one of anger. If you got too close to the riverbank, he would gape and then often charge at you, a huge cascade of water being thrown into the air as you encroached on his space, his territory, his family’s habitat.

He hated the sound of rifle shots. He would panic and gape aggressively, attacking even his own family members if they were too close to him as a shot was fired. Bob was not a passive hippo; he was two and a half tons of muscle. Yet, over the years, from this wild savage fellow he turned into my very special friend. One day there will be a book telling Bob’s story; this is just to let you know a little bit about him.

Bob took three years to be at peace with me and perhaps view me as part of the riverine’s inhabitants. He learned to recognize my voice. I in turn had discovered that sight or scent of me got him mad. Then I just became a dangerous human.

If I talked though, calling him by his name and chatting to him as I would to any other animal, he would calm. It took three years, but at the end of that time I could sit about ten feet from Bob on the river’s edge and he would go about his business as if I was not there.

Bob’s acknowledgement even stretched as far as mating his females while I stood twenty feet away taking photographs. Twice he had fights with other hippos and I stood watching and photographing and he was not in the slightest bit bothered by my presence. Bob would come when I called him. He could be 500 meters away upstream in the Turgwe River. He could be hidden from my sight under reeds. He could be on land opposite me and I would call and he would come. He would move towards wherever I stood. Often he would be moving under water and just a slight ripple of the surface or the light catching his bulk under water would tell me he was on his way. hen a loud roar of expelled water would announce his arrival, his head shooting up and out of the river, his mouth in a huge open-mouthed gape.

Bob had come to see me.

Bob did this to such an extent that during the happy years from 1995 until 1999 safari clients accompanying me were given the most magnificent show. Bob literally performed for these people. If the family were sleeping on land and at my approach, either alone or with safari clients, they began to panic and rush back into the river- all I had to do was talk to Bob. He would stop any panic: his head would come up, his alert intelligent eyes not missing a thing, and he would listen. After a little while of my murmuring greetings he would actually lie down on the sand again and his family would follow his example.

During our life together, Bob became the star of the media. He was photographed and chief hippo in practically every article which has ever been written about these hippos. He was seen on American TV, Australian TV, and British TV and on the Discovery channel. Bob has always been the king and the star of these amazingly wonderful animals.

Bob also saved me on two occasions from almost being killed. I was too blasé in the past, too enamored by the beautiful parts of Africa to look too much at the more ugly sides.

Crocodiles fascinate me, but on two occasions it was Bob who woke me up and made me aware that I was becoming a little bit too familiar with these prehistoric predators. Both times the crocodile could have easily grabbed me and eaten me if it had not been for Bob.

In those days, the main problems we had here were natural and I could sometimes spend six hours each day just studying the Turgwe Hippos, watching them often watching me but also getting on with their lives. It became so easy that I was not even noticed as long as I announced my presence on my initial arrival.

The honor of being in the space of wild animals, of watching them mate, play, fight, groom each other, roll in the water and generally get on with being hippos was all thanks to Bob.

I would speak and he would answer me on more than one occasion, so it could not have been a coincidence. His loud roar of greeting sounded more like a laugh than the scientific term of wheeze honking! Bob would greet me with his loud, most recognizable call. Of all of the hippos, his voice was the loudest and deepest.

When I left the hippos, I would always say goodbye. One does not sit with wild animals for six hours and then just get up and walk off. In my eyes, one thanks them and pays them the respect they are due. Bob always, always called out as I left the group. Several journalists even mentioned this in their articles.

Yes, Bob was so very special.

When on the two occasions I nearly became a meal for the crocodile, it was Bob who let me know that the wily predator was about to plunge out of the water and end my days of hippo observation. The second time it happened, Bob actually went from a quietly sleeping (or so I thought) male hippo into a flurry of movement and a quick mock charge

at what at first I thought was me.

This was over five years after we had become friends, so I was shattered to say the least but then I saw the crocodile swimming away. About a nine foot croc had literally been below the bank where I sat. I had been far too close to the water and he/she could easily have pulled me in.

Bob saved me.

Some people may ridicule this, but over the years I have watched several of the Turgwe hippos let other animals know about danger. Cheeky actually took a goat off of a crocodile into her own mouth. The crocodile had captured the goat as it walked along the edge of the riverbank, then dragged it into the water and drowned it. The croc reappeared with the now dead goat clamped in its mouth. Cheeky, who was then a sub-adult female, attacked the crocodile and reclaimed the goat in her own mouth. She then proceeded to mouth it and obviously realized it was dead. The crocodile took umbrage, managing to grab the goat back and took off, with not only Cheeky but also all of the Turgwe Hippos in hot pursuit.

On several occasions, vervet monkeys have been eating fruits on overhanging branches swinging perilously close to the water. I have seen crocodiles commence their move to take one of the monkeys and I have also watched the hippos either head the crocodile off in another direction, or move fast towards the branch and disturb the monkeys. The same has happened with small antelope drinking at the water’s edge.

Basically, nobody knows why hippos do this. It has been recorded on a couple of occasions on video that they take captured animals out of water and put them back on land. Twice-once in South Africa and the other time here in Zimbabwe- hippos literally rescued impala that had been chased and hurt by painted hunting dogs and ran into water to escape these predators.

Hippos had caught the impala in their mouths and moved across the dam or river and placed the live animal on the bank. On the one occasion, the hippo stood over the impala-which sadly died. The hippo remained, as if breathing on that impala, for over one hour, opening and shutting its mouth and nosing the carcass but never once moving off, just standing as if guarding the antelope.

So Bob’s behavior with me and the crocodiles all made total sense to me.

Bob and I grew together. He has taught me over the years more about hippos than any of the others. Whenever I came to their pool or met them in the Turgwe River, it was Bob who kept the group calm. Bob who greeted me first, Bob who was my King.

Sometimes Bob left his family, which he would do each year. In the old days, before the people invasions and the takeover of the hippos grazing lands by these so-called war veterans and their minions, Bob had two permanent territories. It was to those areas I took the safari clients. For an hour or so, they met a bunch of hippos that were very different than your average group, all thanks to Bob.

It always felt different when I visited his family and Bob was off on one of his male hippo journeys. The space was obviously empty of big Bob and although all these hippos have their own characters and ways it was Bob’s presence that I missed. I would be so overjoyed when he came back to the family.

I would fear for Bob, but not from another hippo. For Bob, I feared man.

You see this area sadly is a sport hunting area, opposite our home, and used to be a bow hunting and photographic area downstream of our home. Now, that part just has squatters, invaders, war vets and no animals, as they have killed so many and the other animals have run away.

I initially feared the safari hunters, for the payment of killing a large hippo for the safari operators is high. A wealthy hunter will pay up to US$12,000 to kill a hippo in his prime. Bob was a candidate: being a bull, more likely to be hurt than a female.

For years I lived in fear of these hunters, as they loved to pull my leg and ridicule me. I became a standing joke for the young trainee professional hunters. They took the mickey of me all the time. The owners would constantly tell me they were going to take Bob. It was their idea of humor.

When you spend hours with an animal, you learn things you never knew. You see that animal for what it is. When you watch it being a father, a fighter, a protector, a clown, and then you think of some person killing him so that they can mount his ancient head upon their wall, far away from Africa where that animal was born, then it hurts and cuts a large hole into your soul. Funnily enough, those were the so-called good days. Those were the days before the problems that we now face.

So, I have always feared man with regards to my Bobby. Yet I am thankful. I am thankful and humbled by his ending. Bob left us as Bob lived. He

died fighting for what was his, a hippo cow in heat called Abe. Another bull ended my old hippos life.

I will not go into detail, but suffice to say I examined Bob and found no sign of man’s ways- no bullet holes, no spear wounds or panga cuts, or dog bites. He lay in a tiny pool of water. He was not lying on his side; he was sitting propped up against a granite rock. His head was actually resting on another rock (this is a position Bob often took as his head was very large so very heavy; any convenient leaning object, animate or live would be used). Often one of his family members became his leaning post.

His legs were folded quite naturally under the bulk of his body. He had been dead for a couple of days, but nature’s dustmen had hardly touched his body. The worms had began their clean up job and one of Bob’s back legs had been slightly eaten by a smallish crocodile, but in general he looked amazingly untouched. In fact, the most incredible thing was his face, and his facial expression. I have always been able to gage Bob’s ways by his face, the way he held his head, how he gaped, how he opened his eyes. Well, Bob had his mouth slightly agape, but it rested on the rock facing the pool where his two females Abe and Wish, and their two calves, Tacha and Pavodok, were living.

There was no sign of pain, or struggle, or fear, or panic, nothing. He looked like he had just given a huge sigh and left us. I even photographed and videoed my Bob for the final time. This may sound macabre, but he looked so beautiful, even in death.

The other bull was with the females. I only saw his nostrils and twice he put his head out of the water to breathe. But on both occasions his movements were so quick that I could not clearly identify him. His behavior is similar to another bull called Happy, but until I see him clearly I will not be sure. It was getting late and the river we had crossed to find my Bob was still soft from the rains and we needed to leave them all and drive back to our home.

Bob had died the way he lived. As a bull, as the King of the hippos. This time he had been maybe a little bit too old, too slow to win, but he will always be the Champion for me.

There is going to be disorder now.

At home, by Hippo Haven, are 16 of the hippos. One male, Storm, is Bob’s son; Storm has just turned six years of age.

If the other bull that killed Bob comes down to this pool he may chase Storm away. Hippo bulls mature by about 8 years of age. Storm is big for his age as he has his father’s genes, but he is still a baby in hippo bull terms. At this moment he is looking after the other hippos but he is too young to become the territorial bull for the family. Then there is Tembia, Bob’s other son. Tembia was born in June 1993 and conceived when I fed the hippos during the horrendous drought of 1992.

Tembia looks so much like his Dad.

He has been living around these hippos for the last year. Spending up until Christmas living in the cemented pan that we built for them back in 1995. Now with the rains having flooded the Turgwe, creating more channels and deeper areas for a single bull to live, he has moved away again.

He is old enough to perhaps try to look after the family but against the size of the bull I saw yesterday he would not remain the territorial bull for this area, if he were challenged.

It will be necessary for me to identify this bigger bull. It could be Happy, or it could be a stranger. It may stay up at the Majekwe weir where it killed my Bob, or it may move down here taking over the main hippo group. The hippos need a dominant bull to live with them. So I can only wait to see what is going to happen. I hold no anger or any resentment towards the bull that has killed my Bob. Bob died as a hippo bull should die. Living free in the wild, not in captivity. Not dying from starvation due to old age, when his lips would not have been able to tear up the grass for him to eat, and his teeth becoming too worn. He did not, thank God, die from the hands of man

Either a poacher, or a “sport hunter” did not hunt him; his head will not adorn anyone’s wall. Bob is still alive in my heart; he will always remain that very special hippo.

He stars in the Trust’s new video “For the Love of Hippos”. He has given so many people wonderful photographs over the years, and his face on my own photos surrounds my home. He is also the Trust logo, the sketch of his face is on the Land rover, and he is our letterhead hippo. Bob can never die but there is, as with any death, a terrible emptiness and heaviness in one’s body, a sinking feeling in my tummy, and aloneness. I sat with his family this morning. Abe and Tacha have returned to the group. So only Wish and Pavodok are still up at that weir with the new bull. The hippos were their same lovely selves. Storm was playing open-mouthed pushing games with his little sister Hope.

Blackface, Bob’s most favorite hippo female slept quietly with her calf Inonde, Odile and Libra- all of them leaning against the riverbank. The rest of the hippos behaved like hippos. None of them appeared to miss my lovely Bob. Missing somebody or something is perhaps just a human emotion. These hippos are far more clever than us. I will have to learn to stop listening for my Bob’s voice. Several times while typing this I have heard the hippos calling like they normally do. I have had to check myself as I found myself listening for Bob. I will learn to get over the pain of him not being around. In a way, my selfishness of wanting him still here is wrong. Bob is still free and probably being a great bull hippo wherever he is right now.

I feel for his foster parents. He was the most popular of all of the Turgwe Hippos. A couple of his parents have actually been here and met Bob.

To you all, all I can say is that he had a good life.

He lived a long life for a wild hippo bull. He became a very famous and important hippo, not just for other hippos, but for us humans as well. He was my special friend he and I had a bond that will be very, very difficult to fill.

Thanks to big Bob there is a Turgwe Hippo Trust, and thanks to Bob I have spent the last 13 years having a very privileged relationship with a very special animal.

Karen Paolillo, Hippo Haven, 5th February 2003, Zimbabwe.

0 Comments